"The machine is not itself creative. The creativity comes from our authors"

Hilary Mason and Matt Brandwein of Hidden Door on working with authors to build AI-powered stories that respect IP

Hello and welcome to AI Gamechangers, your weekly guide to the most creative and practical innovations where artificial intelligence meets the games industry.

Missed us last week? We were busy at the AI Gamechangers Summit in Helsinki, which was a roaring success! We’ll be sharing some of the video recordings in future newsletters.

With that under our belt, today we step into a world where the fun of fan-fiction and roleplaying is reimagined for the AI age. We’re chatting with Hilary Mason and Matt Brandwein, the co-founders of Hidden Door, who are building a narrative platform that transforms beloved books and films into living, replayable story worlds. They have a core philosophy that puts creative control in human hands. Rather than letting language models run wild, they’ve built a controllable AI “games master” that decomposes storytelling into structured beats, ensuring the original creative vision remains intact while fans noodle around in their favourite worlds.

If you’re new here, welcome! Each edition, we bring you exclusive conversations with the innovators reshaping our industry. Our archive is packed with insights, and if you have a story to share, we’d love to hear from you.

Hilary Mason and Matt Brandwein, Hidden Door

Today’s Q&A is with Hilary Mason, CEO, and Matt Brandwein, CPO, the co-founders of Hidden Door. It’s a New York-based studio creating a new kind of story game powered by AI, with handcrafted and pre-generated elements, and made in partnership with authors and IP holders. Drawing on backgrounds in machine learning and product design, they’ve built a platform that transforms a fictional universe into an interactive, card-based roleplaying experience. Hidden Door is backed by Makers Fund, Northzone, Betaworks, Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, Homebrew, and angels Dan Sturman (former CTO of Roblox) and Joshua Schacter (founder of del.icio.us).

In this conversation, the pair explain how Hidden Door balances automation with human authorship, collaborates with creators like Alan Dean Foster and James O’Barr, and envisions a future where players explore infinite yet curated story worlds, like fan fiction that grows with you.

Top takeaways from this conversation:

Hidden Door splits storytelling into many small AI tasks, combining structured narrative beats with a database of tropes and world rules.

The platform never trains on authors’ IP. Instead, its human team crafts editorial adaptations in collaboration with the original creators, so they retain artistic control and get a share of the revenue as players explore.

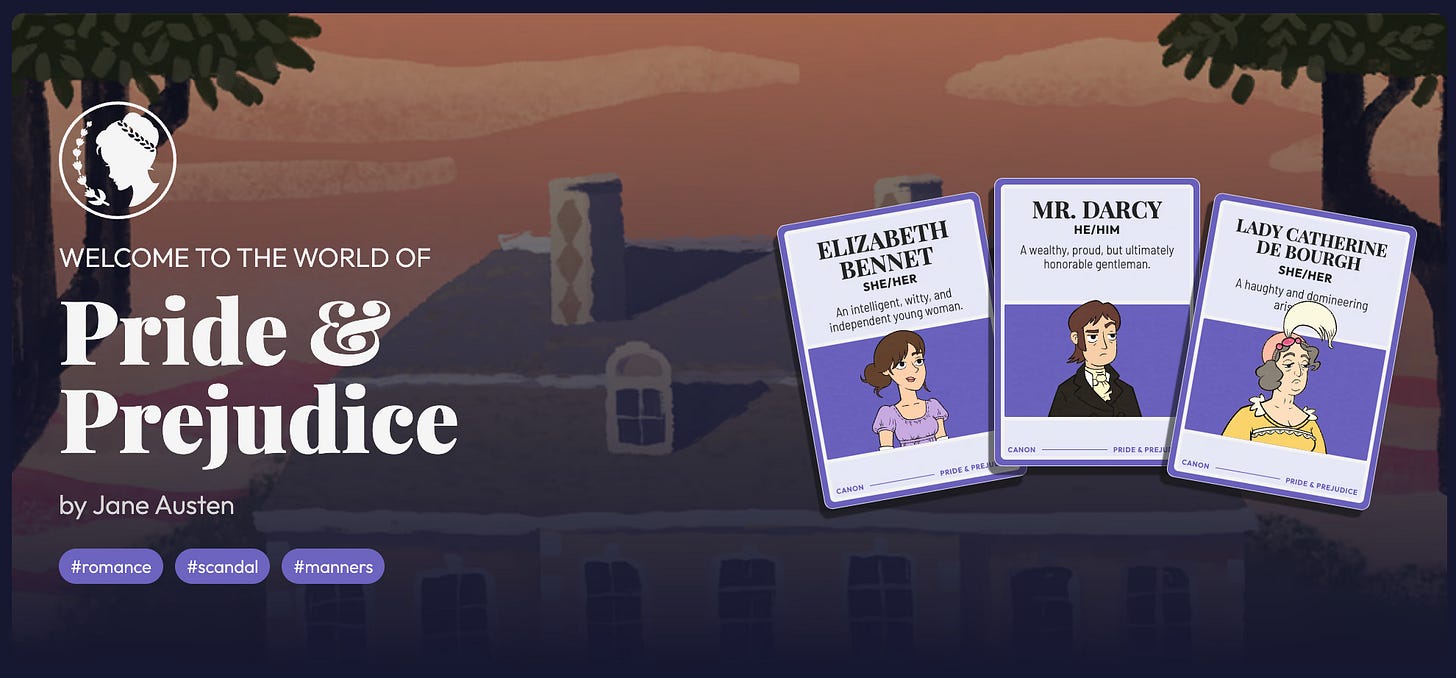

Gameplay emphasises safe, rule-bound improvisation. Players enjoy worlds like Pride and Prejudice or The Crow without fear of toxic or incoherent content.

By merging classic ML, lightweight LLMs, and human editing, Hidden Door aims to make “every path a golden path” and keep human creativity at the heart of the gameplay.

AI Gamechangers: Please tell us how Hidden Door came about.

Hilary Mason: I have a long background in AI. I started as a PhD student in computer science and machine learning in early 2000, and became a computer science professor focused on machine learning. I realised that I actually like building things! In 2014, I started a company called Fast Forward Labs, which did applied AI research and product code development with customers (mostly Fortune 500 and mid-sized companies). We did research and prototypes, including on natural language generation and embeddings. That company was acquired by Cloudera, the data platform vendor; Matt was on the M&A team at Cloudera, and we ran Cloudera’s AI machine learning business unit together for a couple of years.

When we left in 2019, we were both still really excited about what is now called generative AI, but largely that space around summarisations and embeddings. We felt like we were at the beginning of the window to use this technology to build something like an AI “dungeon master”. We both have children who were much smaller at the time, and we wanted to design an architecture so this new GPT thing could make stories that were good, safe and fun. That’s where we began with Hidden Door.

Matt also has a very long background in building search experience, databases, and information retrieval systems. And we’re both long-time gamers and really interested in fictional worlds. When we started, we thought we could pull it off in a couple of years. We founded the company the week before the pandemic started! So the first year was all over the place. It’s taken about five years, but we are really excited and happy about where we are now.

Matt Brandwein: I have a couple of decades building data products, information access. How do we help people make sense of a lot of information? Story systems are kind of around the corner from that. How do we make sense of all the tropes that delight us about stories? How do you help somebody jump into an experience without feeling immediately overwhelmed? So [my background] was not a games context originally, but it all rhymes when you get down to it! A lot of interaction design.

Hilary Mason: Our team also has a very talented game director, Chris Foster, who worked on Rock Band games and Lord of the Rings Online. And an art director who’s worked on Family Guy and the Futurama games. Our team is half games people, half AI people!

AI Gamechangers: Please tell us about the technology behind Hidden Door. Are you using a particular LLM?

Hilary Mason: Rather than taking the approach of building one model to rule them all, creating the only foundation model you would ever need for story, we want a very different approach. We disambiguated and decomposed as many different tasks as possible, and made very deliberate decisions around questions that are impossible to answer quantitatively. Questions you have to answer to build an experience.

“It’s about turning generation problems into ranking problems. You can do generation offline, when you have the luxury for quality control, and ranking in real time. We have people who read and edit and, in many cases, also handwrite things that go in”

Hilary Mason

Whenever I talk to PhD students in machine learning, the question they ask is, “What are you optimising for? What’s your objective function? How do I know if your model is good?” And the answer is… vibes, right?! Players come back because they want to play more stories.

A lot of what we do is decompose the task of what makes a great story game, and then we use a bunch of different systems. I’m a big fan of the fastest, simplest thing that’ll suffice for a given task. And so conceptually, you can think of our system this way: we take text or unstructured input and we model it in a game engine layer, which is really a Postgres database that gets updated every turn of the game, with the characters, their status, their stats, any changes. That lets us run programmatic functions against that database.

We could run a physics simulator if we wanted to. We don’t do a lot of that yet, but we do have a database also of words and phrases and metadata: “What is a cup? What is it made out of? What does it contain? What is its likely size?” And that way, if you say something like, “I put a Ferris wheel in my pocket,” we can say, “No, you don’t!” Because we know that’s too big to fit in a pocket.

Then we use our game and database layer to generate the story that you see. We take all of our handwritten tropes. What is a heist? What is a vampire? What does it mean to be like a person of the cloth? What does it mean to be on a journey? We take that, and add the IP we’re playing in.

We work with authors, film producers and people who are world builders. We sign agreements with them, and then we take the narrative, laws, physics and rules of their world, and we create what we call a world seed (it’s a 100-line Python definition file that maps from their world into the right set of tropes), and then we make rules for things we have to create for them. We can pull them together really quickly. But then we take what our players do, and we throw that all in a soup, and then we say, “Okay, system: what’s the next narrative beat?” The system checks that what the player is trying to do makes sense, based on everything else going around. Is it easy, medium or hard for this character in this situation? Are we trying to end the scene with a goal in mind? Are we trying to let the player find a new adventure, in which case we might be more permissive? All of this is to create the illusion of how a good DM would stop you from going too far off the path in a tabletop game.

Matt Brandwein: It’s important to add that when we work with our content partners, we do not train models on their work. We are always reading the work. And then we have a narrative team that works hand in hand with the partner to effectively write an adaptation, or a set of authorial interpretations of how the player should enter this world.

What kinds of characters can they be? What sorts of plots do we want to put forward? Do we let them go off the rails? If you play Pride and Prejudice (one of our public domain works) like a heist – that’s not a common plot in Pride and Prejudice! But you can have a heist in Pride and Prejudice, because we have the recipes for a heist, and the system knows how to let the player do that, if they pull hard enough on it.

How do you prevent people from going so wildly off the rails that it’s no longer appropriate or good taste?

Hilary Mason: What makes a good story, what makes a safe story, and what makes a fun story? The answer is actually all the same.

We started out asking, “What would it take to make something we were proud to put in front of a kid?” We’re not for kids now, but we started with that. It’s about controllability and interpretability, and the ability for our team to say, “No”.

For us, a heist actually has these beats:

1/ It has the set-up: what are you going to steal? Get your team together. Training for the heist. Case the joint.

2/ It has the “something’s gone horribly wrong” moment, and we’re withholding information from you, the player, as well, to make it all seem horrible… But then it’s going to be okay.

3/ And then you’re going to have the “Did we actually steal the thing?” moment, and you're having a Fast & Furious-style family barbecue or whatever.

We wrote those out because if we didn’t, we would have to rely on the LLM’s model of what a heist is. LLMs are actually pretty good at trope-y fiction, but we don’t control that, and therefore, they’ll do things that can be kind of boring. Aspirationally mediocre heists. Also, if it’s not what our particular author wants, we have no mechanism other than to add into a prompt saying, “Actually, don’t do that thing... or do it more this way.” You have no hard control.

“We have trained a bunch of models. Classic machine learning classifiers. We use embeddings all over the place. We have a bunch of the beats handwritten, and then we’re using an embeddings-based algorithm to pick, so we pre-generate and cache everything we can.”

Hilary Mason

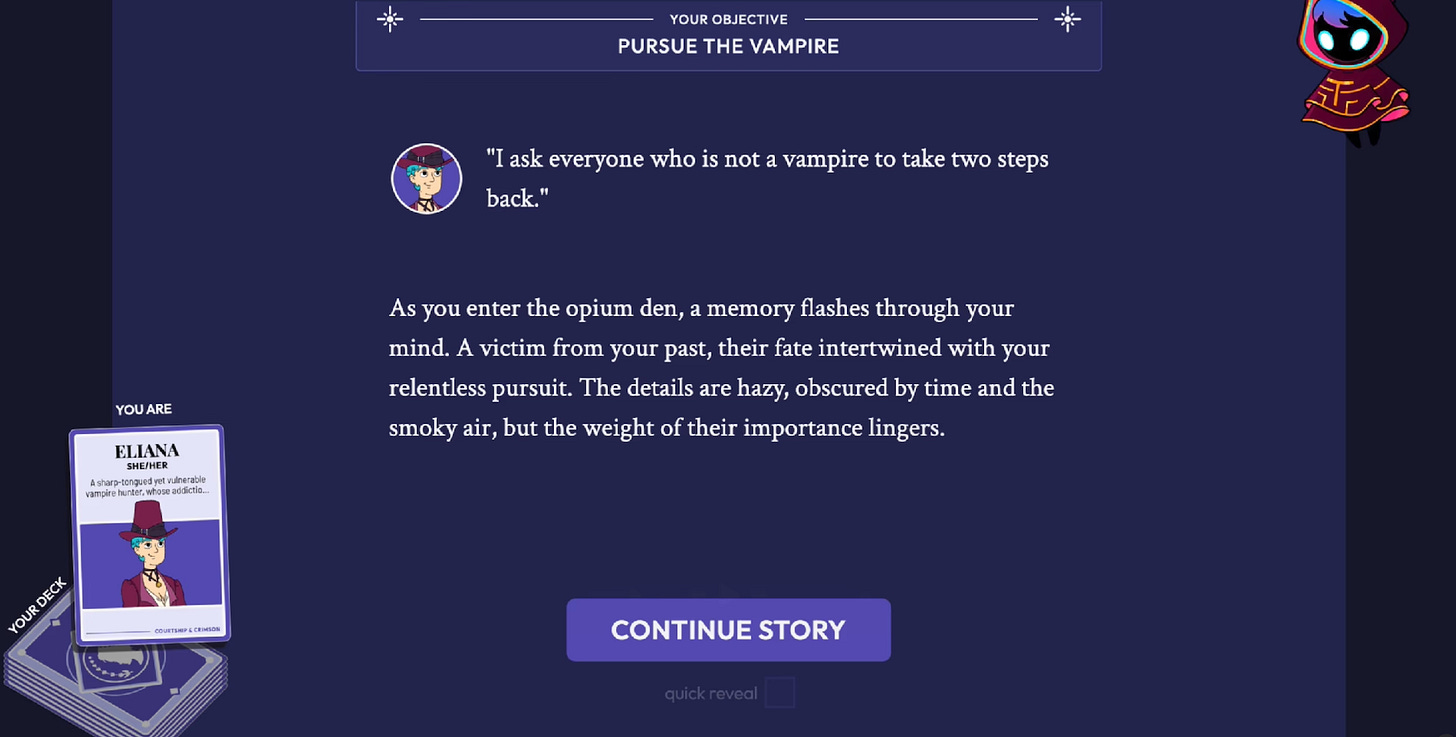

This comes from a place of philosophical belief – and me being in the tech space for a long time – that the machine is not itself creative. The creativity comes from our narrative designers and our authors. Therefore, we decide what a heist is! And we tell the machine what the next beat of the story is. “Here’s what the player has been doing and where it’s going and how other bits of our system have been guiding or directing them.” We set up beginnings for the player, essentially (like, each scene is about five minutes), and we give them the challenge, an objective, and then they get to decide how they want to go through it. They can’t reroute the whole story, though.

And another thing I’ll say here is that if you’re familiar with a lot of the AI roleplaying tools out there, a lot of them are more on the spectrum of writing tools, where you get some generated text. Ours is not that: it is intended to be a roleplaying game experience. You fail, you have to figure out how to recover from that. That’s part of the fun for our player community.

We did an adaptation of The Crow with Pressman Film based on the James O’Barr graphic novel. And we wanted our origin scene for your character in The Crow to be you getting murdered. (Every comic book has you falling in love and your love being brutally murdered, and you come back for revenge.) When we were playing with LLM permissibility, it would not let us murder our players. No matter what. We did a lot of work to be kind of brutal, because that’s the world we’re in – it’s like an R-rated violent movie world.

And you can set that in our system on a per-world basis. We have an “R-rated”-style rating we can use if we have a partnership with a romance publisher. You could [in those conditions] get to the point of making love – you have to opt into that. Then we have platform-wide limits. Within that, our partners get to choose where they want to be. We have very nuanced controls. The Crow has lots of violence but not sex. The romance novel has zero violence, but lots of fun, empowering sex. The LLM does not get to decide what happens.

Can you tell us about the IPs you’re working with? What are your story worlds?

Hilary Mason: We have a few public domain ones. And then we have some partnerships with authors and other folks. The first one we launched was The Crow. We have a partnership coming with [romantic fiction company] 831 Stories. We have a partnership with [sci-fi author] Alan Dean Foster. He’s been the most fun – he has several published and unpublished stories that he’s exploring with us. The first one we’re doing is called Dead Man’s Tale, and it’s this funny story where you tried to commit suicide, but instead ended up with an alien controlling your body. The alien is a tourist on Earth, and so you’re playing this internal monologue.

We have a variety of partners, and we’re bringing another set of partners on after launch. We hope to have new content every month. No surprise, sci-fi authors are pretty excited about this sort of thing, and we have a cluster in romance and “romantasy” too. The motivation from the author’s point of view is that a fan reads their book and still wants more of the world – this is a place where the fan can essentially do controllable but authorised fanfic roleplay, safely, and they stay engaged and excited about that author’s work until the next book comes out. It’s not competing with the author’s books.

We’re still in early access, so we are not charging our players – but our revenue model will be to share revenue back with the authors. So this is another revenue stream for them, using the creative work they’ve already done.

“We’ve been inspired in part by Amazon Audible. You will get a sample, and then you have the ability to enjoy it as much as you like. And that may be individual credits or perhaps a subscription, but that makes the revenue share extremely direct”

Hilary Mason

As to how we work with them: we read the book or watch the movie or read the graphic novel, and then someone on our narrative team (which is very small and mighty) says, “Here’s my first idea for a hook for a player or a fan. Here’s where we think they should enter the world.” We look at the timeline. Who can the players be? When we did our Wizard of Oz adaptation, we said, “You’re going to be a human from Earth in the 1920s who gets swept into Oz.” You can’t play as a Porcelain person!

It probably takes us about an hour, once we have those editorial decisions made, to pull up the first version of the tropes and genres. Then we write the special rules for this world; this is a mix of LLM instructions, language-based rules, but also programmatic rules. (What happens when you die? Do you wake up in the next scene? We don’t want people to lose their characters, but in some cases, we make it pretty bold.)

Matt Brandwein: This is not a game that you win or lose. This is more about connecting to fan fiction spiritually, where it’s about self-insertion and expression and exploration of the world.

To Hilary’s point, we ended up with at least one adaptation, but we may have several. For example, we have several interpretations of Pride and Prejudice, because there are different sorts of sub-fandoms that each want something different from the work.

Hilary Mason: You want to play Pride and Prejudice, but what kind of fan of it are you? We started with the original, and our Courtship in Crimson is basically Pride and Prejudice plus sexy vampires! It’s got a little more of that mature content. We have a vampire Mr Darcy, who’s a little dreamy.

Matt Brandwein: We started out with a “modern film” interpretation of Pride and Prejudice, and then got feedback from early players that they wanted stricter morality and to see gender roles being more clearly enforced, and that sort of thing! We added decorum and dances based on our community wanting to roleplay the manners and rules of Regency society.

It’s important to say that all of our art is hand-drawn by our art director and team, in partnership with our content partner. This applies a bit of our house style, but is also towards controllability, so we know exactly what assets we’re serving up to which players and when.

[Artistic integrity] has been our goal from the beginning. I think players appreciate having a clear connection to the original work, like the creators’ involvement – seeing their fingerprints on it.

Hilary Mason: We have tried to be very thoughtful about creating the best player experience, and also respecting the world-building craft. What really makes each universe unique and fun? Why do you love these things in the first place?

“The thing about open-world RPG games is that they have a handwritten ‘Golden Path’, often with procedural side quests. What we’re trying to do here is create every path you can go on as a golden path. They’re all just as good”

Hilary Mason

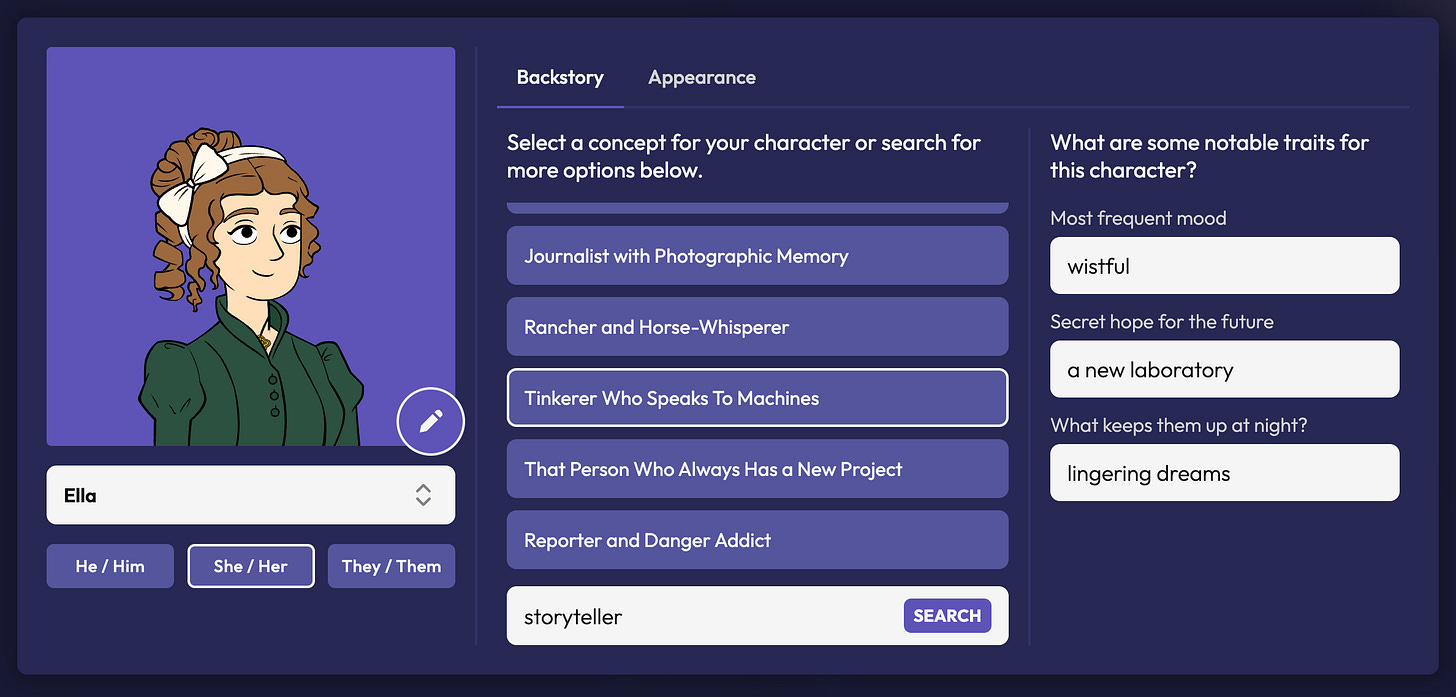

I will also point out that we want this to be very accessible to people who are not really hardcore gamers. Instead of having a stats-based or point-allocation character creation system, we just ask you a few questions about your character, and we go ahead and create it. We use a “card” metaphor everywhere. Everyone understands cards, and then you collect them. As you world-build in your version of the IP, you are collecting the cards for everything and everyone you meet.

And there is a narrator – they will encourage you, mourn with you when you fail at something big, guide you. They are consistent through every game on the platform.

Matt Brandwein: You make your first character [at the start], but eventually you’ll be able to play as any character from your deck. So you can play the villain. You can make new cards as well. And so this lets you play all sides of the triangle: Bond and Blofeld, that sort of thing!

Please tell us a little bit about your gameplay design principles.

Hilary Mason: We come from machine learning. We know an LLM is going to spit out the most average output of what it’s seen in its training data. That doesn’t by itself make a great story. Today, we have bigger context windows, and there are other tools you can use to make it better, but it’s still not good. We’ve been thinking about what the best experience can be, before the hype.

“Our influences also include more than games – we look to community experiences as well. A lot of what makes fandoms work is everybody having their own interpretation and sharing ideas about it”

Matt Brandwein

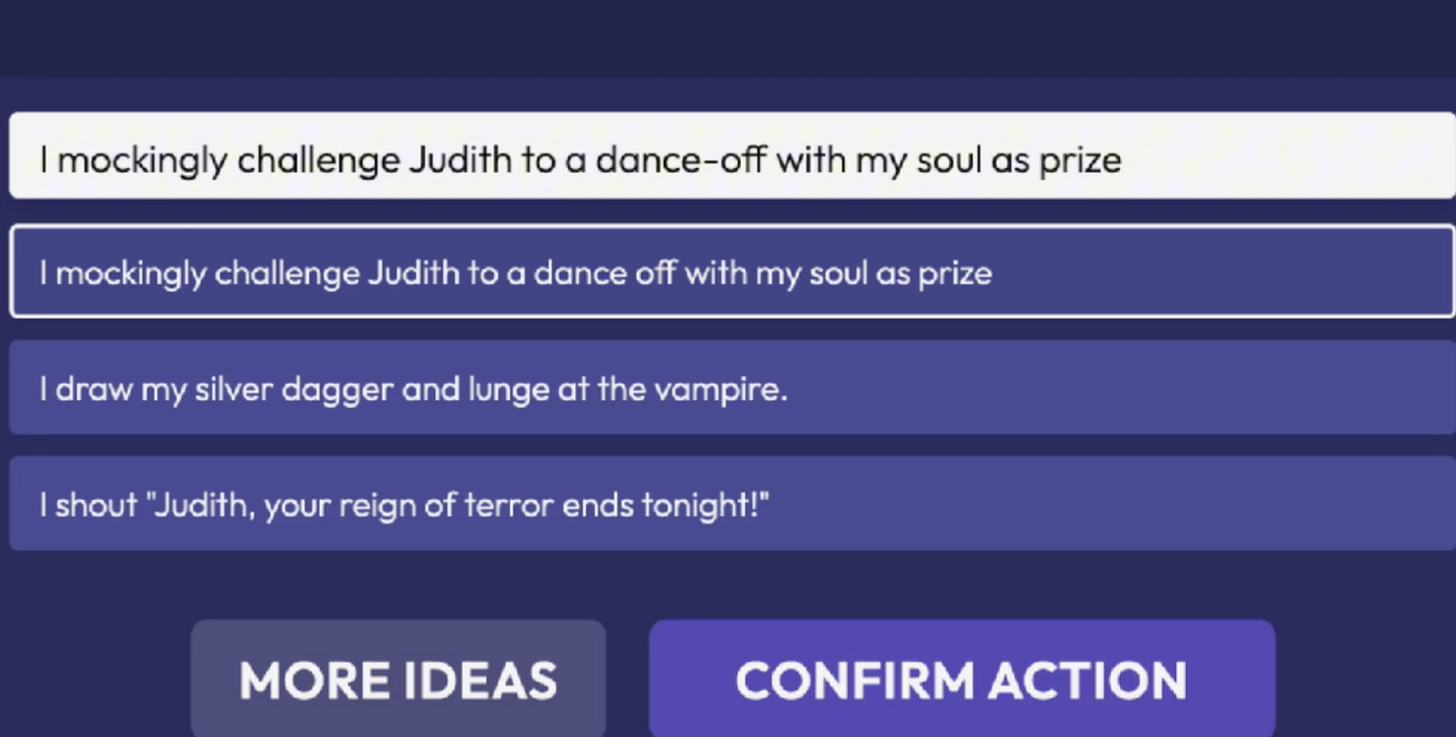

Our UX came about through a lot of iteration. The first version we built just had a box: “Type in what your character is going to do.” And people get writer’s block! They worry about their spelling errors, and they don’t know what to say.

Matt Brandwein: Imagine you’re an ordinary person, and you’re thrown into an improv performance. “Be creative right now!” It’s intimidating. You have a lot of choice if you just have a text box. So we have three suggested ideas.

Hilary Mason: You can press a button for more ideas, too. About a third of those that we give are what a player might do to progress the plot. If you’re playing very earnestly, a third of them are like a little devil on your shoulder, making mischief. A third of them are based on your character’s history. “You tried to swing on the chandelier in the last story. Are you going to try that again?” It ends up being a lot of fun to see those suggestions as well.

Matt Brandwein: Not every object becomes a card. But when the system determines they’re interesting, it’ll make them manifest. Often, we give the players moments to be creative, too. It’s an interesting experience for the player, because sometimes they are sort of the director too, the scene setter. “What kind of story do you want? Who do you want to be?” Then sometimes you are the character, directly roleplaying.

Hilary Mason: We use the word “inspire” because you’re not writing it exactly, but you’re putting in words that are combined with what the scene is looking for to propel the story forward.

Matt Brandwein: It can be like shouting ideas at improv performers. We’re not guaranteeing that we’re going to feature exactly the thing you want, but we’ll try to pull from it in some surprising ways!

It sounds like the experience could be very open-ended. How do you tell a story and keep things on rails when it’s a creative roleplay experience?

Hilary Mason: I consider it a fractal system, in the sense that each turn has its own little narrative tension and arc for each scene. A scene takes five to eight minutes to play, has a beginning that we set up and a provocation. And then it has a set of ways it can end. Some of our scenes are going to railroad our player, for instance, if it looks like you’re about to be murdered, so it’s a chance to open up the next bit of the story.

Matt Brandwein: At the beginning of our Oz world, you must become unconscious so that you can end up in Oz! There are lots of ways to become unconscious, depending on the character you’ve created. A lot of the fun is the system: it’s going to force you to become unconscious somehow.

Hilary Mason: Each scene has a beginning and an end, and then we have a notion of a narrative arc, which is a set of scenes. Stories can be from one to three scenes, or even more. If you’re doing something like a heist, that might be nine scenes total, but we have a break in the middle. We manage beginnings and ends. Stories end, but your world’s overall narrative does not have a fixed endpoint, and the lore of the world updates as you go.

“We want this to be very accessible to people who are not really hardcore gamers. Instead of having a stats-based or point-allocation character creation system, we just ask you a few questions about your character, and we go ahead and create it”

Hilary Mason

Imagine you go into the Wizard of Oz and you burn down the Emerald City. That has changed that world, and the world will still progress as you act in it. You can keep playing in that world as long as you want.

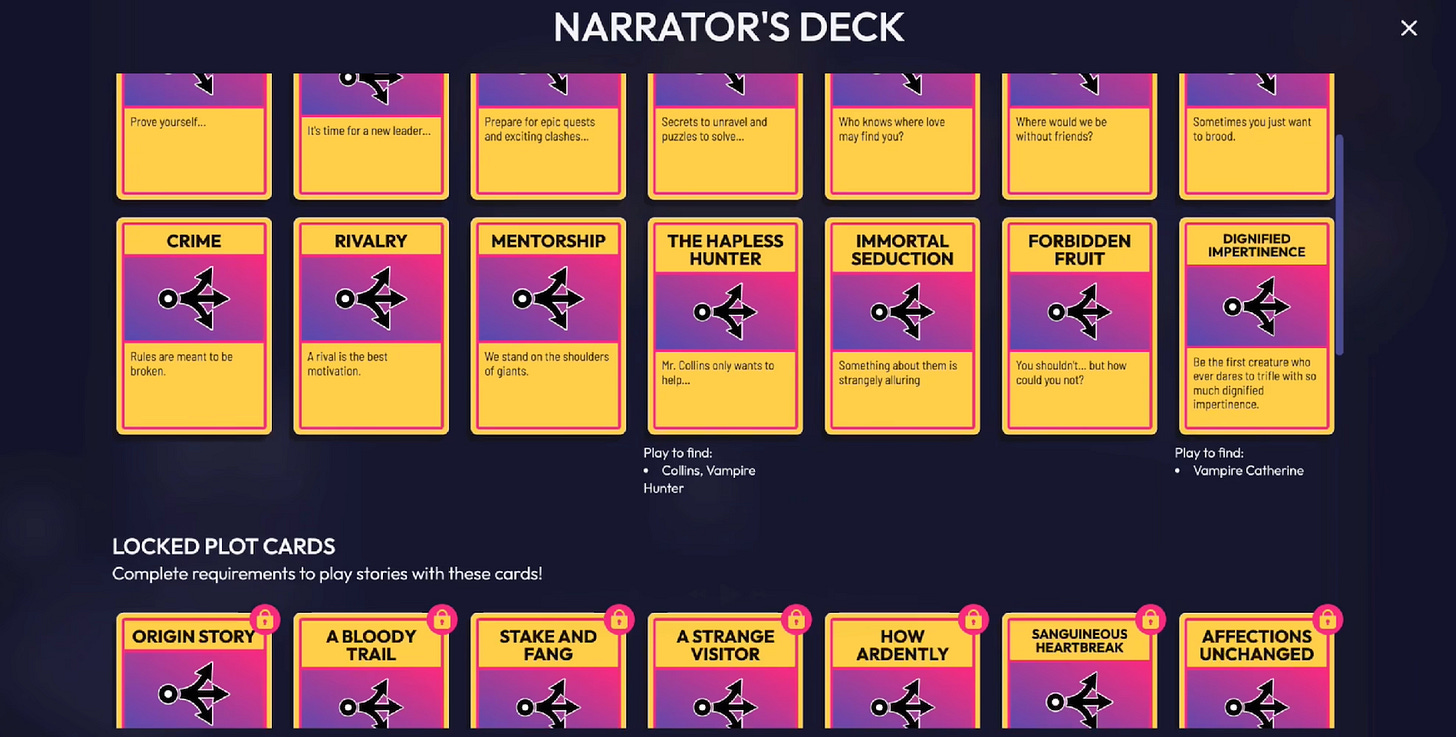

The narrator has a deck of cards, containing all the characters from the original world that you can meet, all the places from that world you can go. We have some players who want to collect them all like Pokémon! But you don’t need to do that. We have other people who have a very firm vision of how they want to play, and they go in that direction.

Matt Brandwein: It’s the same kind of thing for plots. There are characters you can meet, places you can go, but also kinds of stories you can have – a wide variety of things you can do, some of which are canonical to the world. But if you want to do a Fast & Furious heist in Pride and Prejudice, we’ve got a card for that!

“[Artistic integrity] has been our goal from the beginning. Players appreciate having a clear connection to the original work, like the creators’ involvement – seeing their fingerprints on it”

Matt Brandwein

One of the reasons it’s important to keep track of [what’s happening in the world] is not just for coherence in the game, but also – like you, probably – I pick up and put down games all the time, and sometimes I come back after a week and I cannot remember what was going on! I need reminding what I’m supposed to care about and do. With this, we can give you bullet point summaries, and we can do that television serial trick of “last time on…!” It puts you right back in and lets you jump right in from any character’s perspective.

Hilary Mason: At our game table, we can see the narrator’s deck and all the plots available to us right now. There are ones we have not unlocked yet, and ones the narrator has offered us as our next step in this story. We try to offer adventure or romance like the player chooses, but it’s not an infinite set of choices. Each of these has a set of narrative beats, and you more or less know where you’re going to go.

[Our stories] have modifiers – things you earn by playing in a world. If you play the vampire world deeply enough, you’ll earn a “vampires” modifier. (We give superpowers to every one of our players who finds a bug too, as a goodwill gesture!) We let our content partner authors decide what modifier is earned in their world, and it can be branded for them as well.

Our fans want to be able to mash stuff up. Imagine getting a Treasure Island modifier, even though you’re in Pride and Prejudice. Now, some creators are very careful about their IP and are not necessarily excited about [mash-ups]. So this is a way where they can be comfortable that their branding is put in a nice box that says only, “When I play this pirates modifier, it is the rules of ‘pirates’, but applied in the scope of this world.” It lets our players do the mash-up they really want, and mix rule-sets, playing different stories and different characters. It’s a goofball experience, but it’s a lot of fun.

What are your influences from the world of games?

Hilary Mason: I am a huge fan of open-world RPG games like Fallout. Fallout 4 was probably my favourite game of all time. I’m working my way through Cyberpunk 2077 right now. The thing about those games is that they have a handwritten “Golden Path”, often with procedural side quests. The player always knows that those are a grind to get some energy or level up. What we’re trying to do here is create every path you can go on as a golden path. They’re all just as good.

We draw a lot from tabletop roleplaying, too, and the experiences you have with friends. And also, our players are people who read books and like to talk about them. Media is a part of their social experience.

We wondered about building a real-time multiplayer version of the story system, and then we realised that’s not the best experience. You’d have to sit around a table with someone, in which case you should be playing a tabletop game! But what we do is let you take the cards you’ve collected and share them with friends, or post bits of your story and say, “This is how I met Darcy. What did you do?” It’s an asynchronous experience, but still very community-driven.

“It’s important to say that all our art is hand-drawn by our art director and team, in partnership with our content partner. This applies a bit of our house style, but is also towards controllability, so we know exactly what assets we’re serving up”

Matt Brandwein

So our influences come from asking, “What if your favourite author could be your tabletop GM with you and your friend?” Yet, you wouldn’t be embarrassed to have “bad” ideas, because playing with a machine is playing without judgment.

Matt Brandwein: It’s based on that kind of improvisational storytelling experience, but where you don’t have to feel sensitive about being creative all the time.

Our influences also include more than games – we look to community experiences as well. A lot of what makes fandoms work is everybody having their own interpretation and sharing ideas about it. “Here’s what I did with vampire Darcy. What did you do?” followed by “That’s cool, I’m going to steal that!” and so on. With our game, I can take somebody else’s card or story, and I can bring it into my own and remix it later. You end up with these sorts of combinatorial experiences. “This is my favourite version of this world, and I’m going to mess with it until I really like it, and then hopefully somebody else finds it interesting too.” And this is fascinating for our author partners! They get to see, in a controllable way, an interpretable way, what fans are doing with their worlds.

Do the authors you’re licensing from also write for Hidden Door? How much input in the finished game comes from them?

Hilary Mason: They have a lot of input. But as to the form of the hands-on contribution, it really depends on the person. Some of the authors we’re working with are writing directly into our game format, and others are writing us a Google Doc of notes, which we interpret for them. When we sign our agreements, we ask them for a maximum of 10 hours of their time to review [things]. We want them to be super excited about this as an experience for their fans. It’s a mix, and depends on their individual interest and capacity. Most of the partnerships are them playing and sending notes or ideas.

Tell us about the business side of things. Do you do a revenue share split with the IP holders?

Matt Brandwein: Yes, it’s a direct revenue share. The idea is that most of the content on the site will be free to play up to a point (maybe you sample a few stories), and then you will pay for access to whatever world.

We’ve been inspired in part by Amazon Audible with audiobooks. You will get a sample, and then you have the ability to enjoy it as much as you like. And that may be individual credits or perhaps a subscription, but that makes the revenue share extremely direct, and often the fans are coming for exactly one world, but sometimes it’s for a mix of them.

In time, there may be additional bits as well, for additional cards or other things you get to experience.

How do you scale? You could have a great many players, and making API calls to an AI model costs money…

Hilary Mason: There are some assumptions in the question that we have taken a somewhat different architectural approach!

Our system is this: in a given turn, we decompose it into 16 different tasks. They are not all LLMs, by far. We have trained a bunch of models. “How hard is it for this character in this situation to do this thing?” That’s what we now call a classic machine learning classifier. We use embeddings all over the place. So, if we’re deciding what should happen next? In the plot, we actually have a bunch of the beats pre-generated or handwritten, and then we’re using an embeddings-based algorithm to pick, so we run that stuff in RAM, mostly for inference, and we pre-generate and cache everything we can.

It’s not perfect, and we do use LLMs. It’s a variety of different ones, including highly quantised models we can run on our own servers, so our operational costs are actually extremely low for real-time computation.

“This comes from a place of philosophical belief that the machine is not itself creative. The creativity comes from our narrative designers and our authors. Therefore, we tell the machine what the next beat of the story is”

Hilary Mason

We have a GPU machine running in my home office that’s pre-generating and caching things we might use. It’s much cheaper to do it offline, on owned hardware.

I like to tell our team it’s about turning generation problems into ranking problems. You can do generation offline, when you have the luxury for quality control, and ranking in real time. We have people who read and edit and, in many cases, also handwrite things that go in.

Where are you in your roadmap?

Hilary Mason: We are currently in early access. We are very happy with how this world-building experience is taking shape and our early player engagement. We are excited to find more players and more partners, and we really do want it to grow from here.

“Rather than building one model to rule them all, creating the only foundation model you would ever need for story, we disambiguated and decomposed as many different tasks as possible, and made decisions around questions that are impossible to answer quantitatively”

Hilary Mason

We believe this technology lets fans have new kinds of experiences in worlds that they love and appreciate, and we want to build the platform for immersive fan experiences in those worlds and partner with those world creators.

While we have a text-based roleplaying game today, we could imagine different kinds of experiences running on this platform in the future, and this is the first step towards that.

Where do you think this kind of game is going? Are we going to see more games that are more flexible and directed by the user in future?

Hilary Mason: I really hope so, because this is one of the unexplored gaming areas. Using AI to make crappy games is not that interesting. But it is interesting to give someone an experience they wouldn’t otherwise be able to have. We’re not competing with people who are going to write fanfic anyway, or who are going to play a tabletop game. This is a complement to them, and a way to do it in a different modality. That’s the kind of AI game I’m excited about: the ones where we haven’t invented the new metaphors and all the new UX we need for it yet!

Further down the rabbit hole

Some useful news, views and links to keep you going until next time:

The big news in games this autumn was the $55bn acquisition of EA. Could the new owners be gambling on generative AI to cut costs? Tommy Thompson and Rock Paper Shotgun give us a sit-rep.

What’s this? AI search engine and browser company Perplexity just hired a head of games with a mission to work on multiplayer online infrastructure! Hat-tip Benjamin Chevalier.

Upcoming events: there’s the Big Data & AI World conference in Madrid on 29-30 October, then from there you’ve got to hop over to Seoul for PGC Summit Korea on 31 October.

Meanwhile, Supercell’s Global AI Game Hack is later this week, from 24th to 26th October. Join in from anywhere or take a seat at their new place in San Francisco.

Ready to download! Q&As with CEOs from Brimstone AI, NAK3D, AI Guys, Wishroll, Saga and more feature in the free AI Gamechangers ebook 2.

The new president of SAG-AFTRA is actor Sean Astin. He’s already issued a statement about the synthetic character “Tilly Norwood” and OpenAI’s Sora 2.

AI startup General Intuition raises $134m to train smarter game bots and NPCs using billions of gameplay videos from Medal.tv

Ego AI raises $6.7m to replace “flat, scripted NPCs” with characters that act, react, and remember like real players.

“AI feels like the perfect co-founder.” Industry veteran Joakim Achren (co-founder of Next Games, now a Netflix studio) has launched a new venture developing “all sorts of software that leverage the power of AI.”

At the time of writing, Tron: Ares is in cinemas. It has not done well. But this threequel’s story sits (loosely) at the intersection of AI and games, and if you have a fondness for the ’80s original, it’s worth a couple of hours.